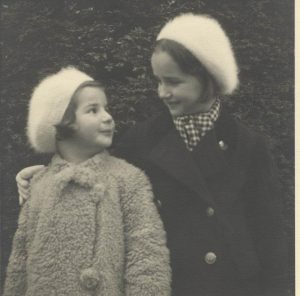

The story Ilse Gray tells is a pebble polished from many tellings. The factual calm covers up the horror and despair that people lived through. Ilse and her sister, Eva, were on one of the first Kindertransport trains to leave Vienna in December 1938. But six-year-old Ilse, unlike Eva who was three years older, did not understand that she might never see her parents again.

The story Ilse Gray tells is a pebble polished from many tellings. The factual calm covers up the horror and despair that people lived through. Ilse and her sister, Eva, were on one of the first Kindertransport trains to leave Vienna in December 1938. But six-year-old Ilse, unlike Eva who was three years older, did not understand that she might never see her parents again.

In the thirties there were about 200,000 Jews in Austria and 90% of them lived in Vienna. By 1945 some 120,000 had escaped and 65,000 had died.

“I was born in Vienna in 1932”, Ilse told me . “My father, Karl Goldberger, was an ear, nose and throat specialist. We lived in Marc-Aurel-Strasse on the edge of the old Jewish quarter. When I was three, my parents divorced. A year later my mother re-married and we moved into a large flat in Hietzing, near Schoenbrunn Palace. My stepfather, Heinrich Krott, was a respected dental surgeon.”

Then, on 12 March 1938, came the Anschluss, the annexation of Austria by Germany, and the process of Aryanisation began. Immediately, Jewish homes and shops were plundered, Jews from all walks of life were dismissed from their jobs and gradually robbed of their freedom, blocked from most professions and shut out of universities. Those in private practice, like Ilse’s stepfather, were only allowed to treat fellow Jews. “We weren’t at all religious. I didn’t know anything about being a Jew until the Anschluss. My older sister was already at school but from that point on they didn’t allow Jewish children to attend ordinary schools so Jewish teachers set up schools for Jewish kids. I started school when I was six in April 1938.”

These were the days before large numbers of Jews were sent to concentration camps and Nazi policy was to get Jews to leave. But they had to queue every day for hours to get an exit permit from the Central Office for Jewish Emigration, established by Adolf Eichmann. This was a deliberately tortuous process with no certainty of getting a visa. If you got one you were not allowed to take any money with you and property was confiscated and families evicted. “It was clear that we would no longer be able to live in Austria and my parents applied for visas to emigrate to Britain. Also, our flat was requisitioned for use by a senior Nazi official. My mother and stepfather didn’t know what to do until my father suggested that we all move into his flat in Marc-Aurel-Strasse.”

The climax came with the Kristallnacht pogrom of 10 November 1938. Synagogues in Vienna were destroyed, Jewish men and women were forced to scrub the streets, shops were closed down, and over 6,000 Jews were arrested, the majority deported to the Dachau concentration camp. “My father and stepfather escaped being taken away due to an amazing coincidence. The morning after Kristallnacht, Eva and I were going to school when we were stopped on the stairs by two young Austrian SS men. They sent us back up to our flat saying they would follow. My father opened the door when they knocked, and as he was questioned about who lived in the flat, he asked one of them, ‘Don’t I know you?’ Shamefacedly, the young man replied ‘Yes, my parents were patients of yours.’ He then told his companion they would come back later. But they never did.”

The Krott family still had no visas, so when Ilse’s mother heard about the Kindertransport they decided to send her and Eva to Britain. “When parents put their children on those trains they really thought they would never see them again. Both my mother and Eva thought that. The family came to the station to see us off. They all thought: ’At least get the children out’. The Quakers’ office in Vienna arranged our transport. We were accompanied by the brilliant, and brilliantly named, Miss Hope.”

“The train went through Holland and once we were across the border we all cheered. We landed at Harwich and travelled by train to Liverpool Street. We were to go to a foster home in Cringleford, a little village near Norwich, but stayed a few nights with Miss Hope in Park Village East.” This was the start of Ilse’s lifelong connection to Camden: for over fifty years she and her family have lived in Princess Road. In Cringleford the sisters soon learnt English, went to the village school and made friends. Meanwhile, the rest of Ilse’s family – sadly not all of them – were still queuing for exit visas. “My mother got her visa in the spring of 1939 and came over with my baby half-sister, Heidi. But my stepfather did not; he went to Helsinki and got out from there, arriving in London within a day of my mother. My father – both Jewish and an ex-member of the communist party – hung on until friends warned him the Gestapo were after him. He crossed the Alps by bus to Genoa and got on the first boat to Uruguay. He lived in Montevideo for the rest of his life, but took Eva and me to Vienna in the early fifties and also came over to London. His parents stayed in Vienna, looked after by my aunt who, after they died in the Jewish ghetto, was transported and died in a concentration camp. My mother managed to get her parents to London three days before the beginning of the war with the help of a kind man she met on a bus who offered to sponsor them.”

With little money, Ilse’s parents lived in one room in Belsize Square while Dr Krott re-took his dental examinations. So Ilse and her sister continued to be fostered in various parts of the country until they could be reunited with their family in their new flat in Hampstead. However, not for long. They were evacuated with other New End School children to St. Austell in Cornwall until late 1940 when a stray German bomb was dropped nearby. “My mother decided that if Cornwall was not safe we might as well all be killed together and we returned to London, just in time for some of the biggest air raids of the Blitz! We stayed in London for the rest of the war. Because we had such good foster parents we had lots of happy and interesting experiences. And, of course, we were very lucky to be reunited with our parents and Heidi. Most Kindertransport children never saw their parents again.”

By The Mole on the Hill