Article by Jim Mulligan.

Us moles always duck when a helicopter goes over The Hill. Why? I’ve explained before, us moles have a collective memory that extends over time and place. Our ancestors in the Philippines learned to duck when the helicopters went over for Apocalypse Now. For weeks on end, they flew for the film every day. It was keep your heads down, lads. Still is, if you ask me.

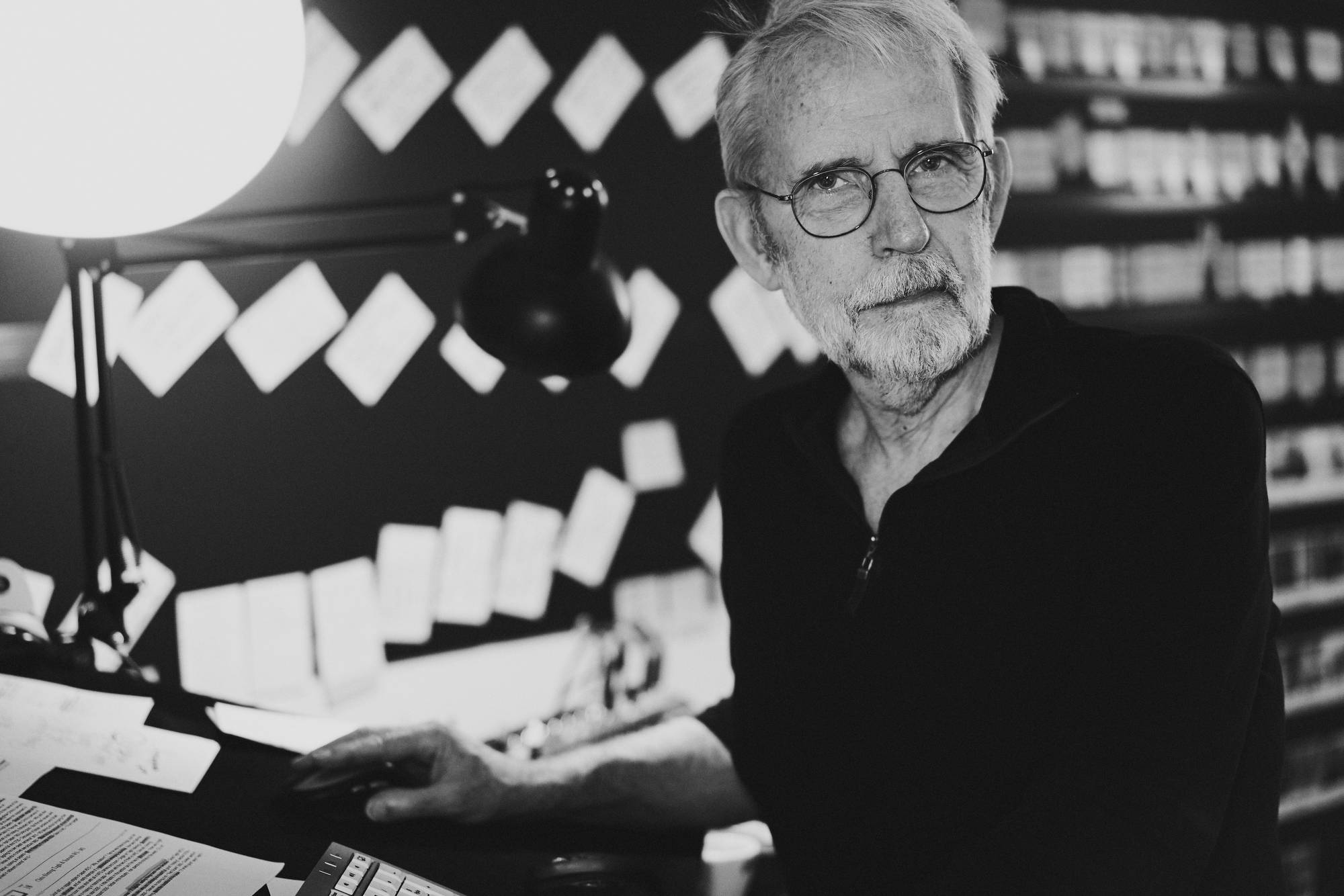

All relevant to Primrose Hill resident Walter Murch. Never heard of him? Of course you haven’t, because he is a living oxymoron. The nine-times nominated and three-times Oscar and BAFTA winner for film-editing and sound-mixing can walk down the street and only be recognised by his friends. Seventy-four-year-old Walter wears his success with nonchalant ease. “I don’t think it touches me in any deep way. The Oscars and BAFTAs are in a closet somewhere back in California.”

Walter was born in Manhattan. His father was an artist, his mother the daughter of Canadian medical missionaries in Ceylon. “I didn’t have a religious upbringing in any conventional sense. We were certainly not affluent but we always had enough to eat, and my dad supplemented the income he got from painting, by teaching and doing covers for Scientific American and other commercial art. My mother worked as a church secretary, and that also helped.”

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]I was aware of tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States, and that there was this atomic bomb threat and McCarthy was somehow connected to that[/perfectpullquote]

When Murch was about ten, Senator McCarthy was at the height of his powers: waging an intense war on anyone who appeared to be tainted by communism. “Even as a ten-year-old, I was aware of the McCarthy hearings. It was the first inkling I had of how politics can divide people. We lived in an apartment building and I began to hear whisperings. I was aware of tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States, and that there was this atomic bomb threat and McCarthy was somehow connected to that. And I sensed that there were people in the apartment building who were McCarthy partisans, and my family were not. I was aware of a difference. We were not all pulling in the same direction. It was a little confusing.”

Vietnam

And then there was the Vietnam war. Walter’s first induction was in 1961, when he was eighteen. “I was given an induction number, but I didn’t serve in the army. I was a student at university at the time, so I got a deferment. I was always ahead of the draft, not by any plan; but when they started drafting students in 1965, they did not include those who were married. And by then Aggie and I were married. Then they started drafting married students, but not if they had children. And by that time we had a son. Then they introduced the lottery, but my number never came up.”

Not for the first time or the last time, the beloved Aggie was there to support Walter. They met when he was studying in Paris and she was a student nurse at the Royal Surrey General Hospital in Guildford.

There’s a romantic story involving a beaten-up Matchless 350 motor bike. Walter went to pick up the bike in Guildford. Aggie opened the door, and 54 years later they are still married. “The film world is a dangerous territory for the eco-system of marriage. I would put the overwhelming percentage of our success on Aggie. The underlying thing in the film business is that there are long hours of work and sometimes geographical separation – you might be on location for months and this is difficult, especially if you have children. It is dangerous, I guess, for certain marriages. We are still sometimes apart for months at a time, but we write to each other every day. It used to be actual letters, then it became faxes and now emails or texts. I would recommend it. That slightly delayed interaction is a very good thing.”

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Walter Murch’s accomplishments make him one of the most respected and sought-after figures in the film industry[/perfectpullquote]

Walter Murch’s accomplishments make him one of the most respected and sought-after figures in the film industry. For the soundtrack of Apocalypse Now in 1979, he had to create and invent the technology that Francis Coppola envisioned. They moved from monophonic to six-track split-surround sound. This system, now called 5.1, became the standard in the film industry. The engineering was so innovative and complex that they had to build a new sound studio in San Francisco.

Walter won his first Oscar for Best Sound for Apocalypse Now. And ten years later, it was two Oscars (Best Sound and Best Picture Editing) for The English Patient. Film buffs will be able to reel off the other titles. [or see Walter’s IMBD listing]

Return to Oz

But what about the other things? Walter wrote and directed only one film, Return to Oz. “It was not commercially or critically successful when it was released in 1985. Regrettably, because everyone put a lot of great work into it.

We shot the film here in London at Elstree studios. All the post-production was here as well. I made very good friends on the film. I wish it had been a bigger success at the time, and I have not directed another feature film since. But it has a popular second life now as a cult film, thanks to DVDs and other modern release formats.”

We shot the film here in London at Elstree studios. All the post-production was here as well. I made very good friends on the film. I wish it had been a bigger success at the time, and I have not directed another feature film since. But it has a popular second life now as a cult film, thanks to DVDs and other modern release formats.”

And don’t forget that Walter has written the definitive text on film editing, In The Blink of an Eye; he translated The Bird that Swallowed its Cage, by Curzio Malaparte, from the Italian; and he edited the award-winning documentary Particle Fever about the search for the elusive sub-atomic Higgs Boson that was finally discovered at CERN in 2012, while they were still filming. Very fortunate.

And now Walter and Aggie live in Primrose Hill. While he was working on The Talented Mr Ripley with Anthony Minghella in Camden, Aggie had asked him to look for a place in London. “I was walking down Gloucester Avenue. And in an estate agent’s window, I saw a picture of the interior of a house with a small gas-fired iron stove, which reminded me of our first home – a houseboat on San Francisco Bay. Following the agent’s directions, I said if that’s the house with the stove, I’m interested. It was. And we have lived there ever since.”

A frozen dance

Walter stands at a desk when he is editing. It is meticulous work, a split second at a time. Repeat. Select. Repeat. He uses images to describe what he does. It is a voyage, a marathon. The architecture of a film is a frozen dance. It is making something with pieces of jewellery. Or a mosaic. A mental house of cards. He works long hours without flagging. He gets home late. “It doesn’t seem extraordinary to me. Once you are doing it, it is what you have to do. To somebody not familiar with the process, it looks like endless repetition, the same thing over and over again; but I am making small changes here and there. You have to have a vision of the overall landscape. But you also have to pay attention to very fine detail. That appeals to me. I like both the breadth of work and the essential detail.

Iran 1953

At the moment Walter is working on a documentary centred on the coup d’état that happened in Iran in 1953. “The democratic government at the time, under Prime Minister Mossadeq, was a brief window of democracy in Iran. But Mossadeq had nationalised the country’s oil, upsetting the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company which was 51 per cent controlled by the British government.

That was an issue of concern to the powers that be: the Attlee and then the Churchill governments here, and subsequently Eisenhower in the USA. They all thought that nationalisation would set a bad precedent. If this took hold, other countries might also nationalise their oil. Only Mexico had done it previously, just before the war. There was a struggle to rearrange things. Mossadeq, the prime minister in Iran, wasn’t going to back down; and eventually, the decision was made to stage a surreptitious coup against him and install the Shah, who was the constitutional monarch and ultimately became a dictator. We are looking at what happened and how it came to happen and what the ramifications have been, up to the present day. It’s a very ambitious film that has taken a few years so far, but we hope to complete it this year.”

America

At the time of the McCarthy hearings, President Truman described what was happening as “The rise to power of the demagogue who lives on untruth”, and Walter sees similarities between what was happening then and now.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Being a US citizen at the moment is very disorienting.[/perfectpullquote]

“Being a US citizen at the moment is very disorienting. Whatever you thought of Secretary of State Tillerson, his firing is unprecedented. And he was fired by tweet. Trump didn’t even talk to him personally. It’s given me a deeper understanding of the troubles that Germany went through in the 1920s and 1930s. The situation under Trump isn’t yet fascistic, but there are parallels. It’s now easy to see how that kind of demagogue can get a foothold in a democracy, seize hold of the people’s imagination by subterfuge and produce chaos and violence. It’s similar to the divisions in this country about Brexit. Politicians are not known for their truthfulness, but this is several orders of magnitude worse than usual. Lies are told in a chin-jutting way. ‘Take that!’ It challenges your imagination to know how to deal with it.

What will happen once Trump is gone? I don’t know if the damage is fully reversible. Germany did recover from Hitler, but only after the lessons of a world war and many decades, and it’s still an ongoing process. It’s all about education and the acceptance of responsibility.”

Photo by Benjamin McMahon