Local historian Martin Sheppard examines how access to Primrose Hill has been in flux since the nineteenth century

At night during Covid the usually peaceful summit of Primrose Hill became a venue for very loud music and drug dealing, largely beyond the police’s control. Since the end of the pandemic there has been a heated debate between those who want the park closed at night and those who have hoped to restore the status quo with no gates. This debate has been brought into sharp focus by the murder of sixteen-year-old Harry Pitman, stabbed to death in the middle of a very large crowd watching the fireworks on top of the hill on New Year’s Eve 2023.

At present the park is shut by the police, using temporary gates, between 10pm and 6am on Friday, Saturday and Sunday nights. Permanent gates are due to be installed, but it is unclear when these will be closed in the longer term.

Some of those in favour of the freedom of keeping the park open remember the campaign of 1976, when local campaigners resisted the attempts of the park authorities to instal gates. Early Primrose Hill activists even removed a number of the gates, which then mysteriously disappeared.

Both of these episodes are recent developments in a much longer story. The boundaries, fences, gates and hedges of Primrose Hill have all changed over the years. Parish marker stones on the Hill still recall that the Hill lies in three different parishes: those of Hampstead, St Marylebone and St Pancras.

Nineteenth Century

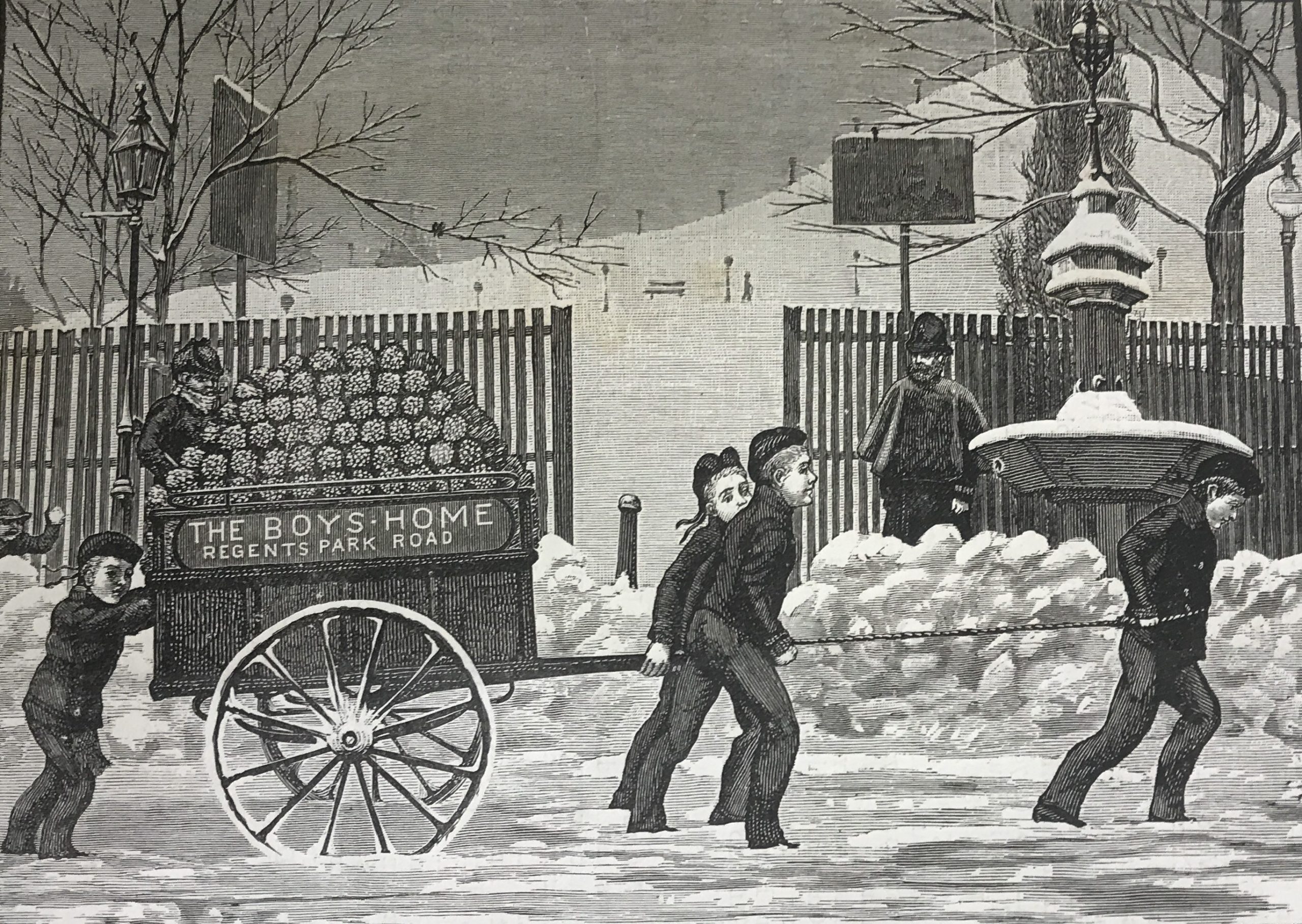

Before Primrose Hill was bought by the government in 1840, nearly all of it was owned by Eton College and leased out for grazing, but the fences were in very bad condition, ‘occasioned by the great stock of cows fed upon the farm and, being so near the metropolis, the wood is daily stolen and carried away’. After the Hill was opened as a park in 1842, these fences, together with the existing hedges and trees, were removed by the Department of Woods and Forests, leaving the landscape bare. This approach was rationalised in the longer term by the contention that Primrose Hill should be deliberately kept open and wild, to contrast with the artificial and manicured Regent’s Park. Initially the boundaries of the Hill consisted of wooden three-rail fencing reused from Regent’s Park, with walls and iron railings on its western boundary. Most of this early fencing was replaced by oak palings by the end of 1845.

A more lasting restriction of access to Primrose Hill dates also from before 1850. There were once many paths crossing Primrose Hill. Nicholas Crane has even identified a section of an ancient road, running towards Swiss Cottage and detectable only in dry weather, on the south-west slope of the hill. These rights of way were, however, stopped by the Portland and Eyre Estates, wary of the threat that rough visitors to the Hill might have on the reputation of their housing developments. This explains why Primrose Hill has so little connection with its immediate neighbour, St John’s Wood. It is no accident that there is no public access to the Hill between St Edmund’s Terrace and Elsworthy Terrace.

A potential addition to the park was lost in 1890 when the Middlesex and Eton Cricket Ground, covering over eleven acres and immediately adjoining Primrose Hill, disappeared under the Willett development of Elsworthy Road and Wadham Gardens. It was unusual in having inside the ground the very sizable vent-shaft of the Primrose Hill Tunnel. A fund to save it as a cricket field failed to raise the £50,000 required; and neither the government nor the local parishes stepped in to enable the land to be added to Primrose Hill.

Twentieth Century

The oak palings around Primrose Hill, which had been put up in 1845, were in poor repair by 1913. Although iron fencing was planned as a replacement, the scheme was postponed during the First World War and then never implemented. In the late 1920s, the London Society and the Committee of London Squares ran a campaign to remove fencing around public spaces. As there were no gates to Primrose Hill, the existing fencing served no obvious purpose, while removing them (which cost nothing to do, as the contractor took the wood in lieu) also saved the cost of erecting a replacement. The fencing was removed in July 1929, other than around the gymnasium and playground, and where there was a steep bank in Primrose Hill Road. Some, but not all, of the railings then on top of the Hill were removed at the same time:

A flock of sheep, feeding in both Regent’s Park and Primrose Hill, was used for many years to keep down the length of the grass. Because there was no fencing round Primrose Hill after 1929, sheep had to be brought there and returned to Regent’s Park during the day, as they could not be left on the Hill overnight.

During the Second World War much of the top of Primrose Hill was fenced off around the anti-aircraft guns sited there. After the war, a new installation on top of the hill, a solid aluminium viewfinder unveiled in 1953, caused an unexpected amount of trouble. It proved a magnet to vandals, who had already damaged it by early May 1953. Neither a perspex cover, added in 1957, nor special armour-plated glass by Pilkington Brothers, fitted in 1960, provided adequate defence. Finally, the park admitted defeat and the viewfinder was removed in March 1962. The damage to the viewfinder had another, wider repercussion. Threatened by repeated hooliganism, the Ministry of Works decided to replace the fencing around the park, which had been open since 1929. Chain-link fencing was accordingly put round the park in 1954, but it was noted that ‘the Minister has agreed not to close the gates at night pending a review of the behaviour of the public at night under the new conditions’.

Turning from fact to fiction, Ruth Rendell in her The Keys to the Street sets scenes in and around Primrose Hill. A series of tramps, and then a dog-walker, are murdered. One of the victims, a tramp known as Pharaoh, who is obsessed with collecting keys, is found impaled on the railings on the north side of the hill facing Primrose Hill Road. It is tragic that this fictional murder should now have been followed by the real murder of Harry Pitman.